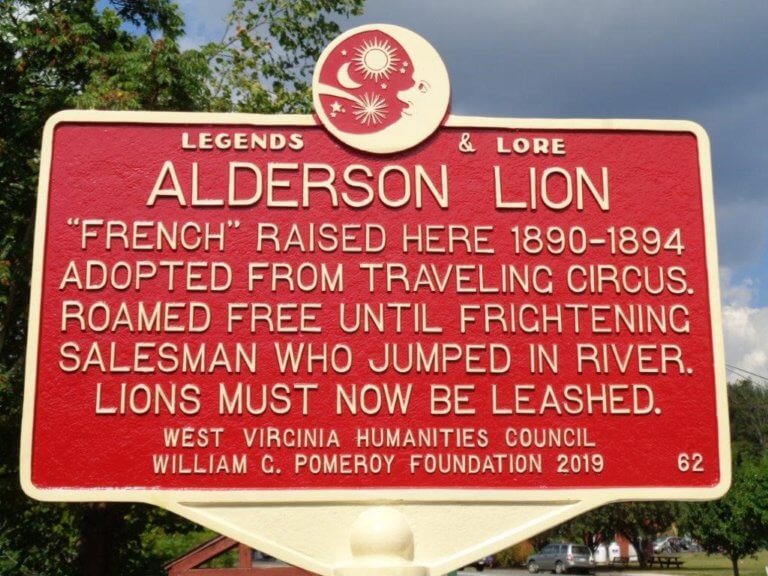

ALDERSON LION

- Program

- Subject

- Location

- Lat/Long

- Grant Recipient

-

Legends & Lore®

-

Folklore

- 205 River View Rd, Alderson, WV 24910, USA

- 37.725382, -80.6411498

-

Alderson Main Street, Inc.

ALDERSON LION

Inscription

ALDERSON LION"FRENCH" RAISED HERE 1890-1894

ADOPTED FROM TRAVELING CIRCUS.

ROAMED FREE UNTIL FRIGHTENING

SALESMAN WHO JUMPED IN RIVER.

LIONS MUST NOW BE LEASHED.

WEST VIRGINIA HUMANITIES COUNCIL

WILLIAM G. POMEROY FOUNDATION 2019

It’s not often that a town has to create an ordinance stating that a person can be punished by fine if they let their lion run around without a leash. In Alderson, West Virginia, however, they ran into just that problem. Thanks to a passing circus, one resident of Alderson became the proud owner of lion that soon became a fixture in the town, until an unfortunate scare involving a traveling salesman forced change.

The town’s unusual story was told in the West Virginia Review in the March 1941 issue, where it was stated that it all began when a lioness in French’s Great Railroad Show gave birth to five cubs. As it happened, she gave birth in Alderson, but three of the cubs died shortly after and the other two were unwanted by the show. The show runners didn’t want to pull the lioness from the performance in order for her to nurse the cubs, so they were looking for a way to get rid of them and found an Alderson resident willing to take them. The resident was said to be Mrs. Susan Beabout, and despite one dying, the other was able to grow and thrive. Mrs. Beabout raised the lion cub with her house cat, Tabby, and soon the two became close friends, with the cub even taking Tabby into his mouth and carrying her like a kitten. It apparently got to the point where all that could be seen “was the cat’s head on one side of the lion’s huge jaws and the hind feet and tail on the other.”

This playful behavior was not just reserved for Tabby, and the Review reported that many of the town’s children enjoyed playing with the lion, stating that nobody in town thought it was “unusual, so to speak,” to have a lion roaming around. While the residents of Alderson had grown accustomed to Leo, as he’s referred to in the article, visitors to the area were more likely to get a shock. As the story goes, there was a traveling salesman that had stopped in Alderson for the night and decided to go for a walk. He was crossing from the south side of Greenbrier River to the north when he was said to have heard something following behind him. Upon turning around, the salesman came face to face with Leo, who “evidently wanted to play, and to sniff the stranger to those parts.” Unaware that the lion standing in front of him was rather docile, the salesman took off running and jumped into the river. The salesman didn’t stop running until he made it to the local doctor’s house, where he promptly passed out from fear.

The visitor’s reaction to seeing Leo “caused a great deal of public speculation” regarding the lion’s roaming, and it was stated in the Review that the town council met to pass a new ordinance. It then became law in the town that no lion was “to run at large on the streets,” and if broken, it was punishable by a misdemeanor and fine. This new law forced Mrs. Beabout to fence in her yard and put bars on the windows throughout the lower level of her house, though she soon realized that she would no longer be able to care for Leo. She was eventually able to sell him to the National Zoological Park in Washington, D.C., and in a book written by one of the keepers, Wild Animals in and out of the Zoo (1930), Leo was said to be “greatly admired by the public.” His demeanor was described as “gentle and affectionate,” and his keeper said that Leo would even leave his food to come see him, something the keeper had never seen done by another lion.