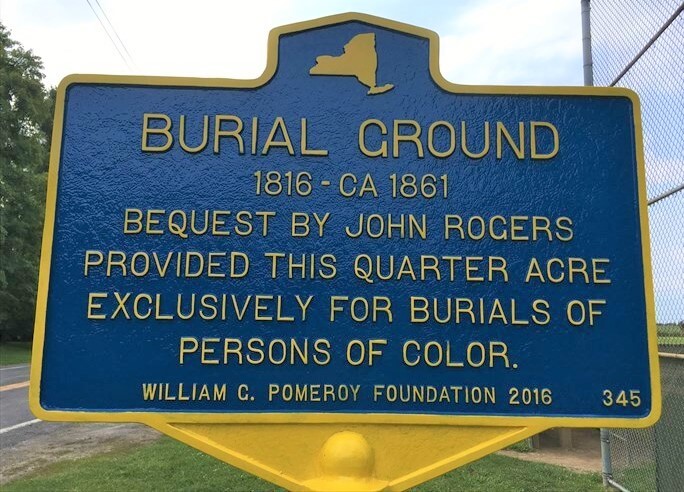

BURIAL GROUND

- Program

- Subject

- Location

- Lat/Long

- Grant Recipient

-

NYS Historic

-

Cemetery

- 17 Rothermel Ave, Kinderhook, NY

- 42.39595, -73.704856

-

Village of Kinderhook

BURIAL GROUND

Inscription

BURIAL GROUND1816 - CA 1861

BEQUEST BY JOHN ROGERS

PROVIDED THIS QUARTER ACRE

EXCLUSIVELY FOR BURIALS OF

PERSONS OF COLOR.

WILLIAM G. POMEROY FOUNDATION 2016

Upon his death in 1816, Kinderhook resident, John Rogers, bequeathed a small portion his land to be used exclusively for the burials of persons of color. This burial ground was used from 1816 until sometime around 1861.

The history of African Americans in the state of New York is discussed in an article titled “Slavery and Freedom in New York City” by Eric Foner, and it began with Dutch colonization in what was then known as New Netherland. Published on Longreads.com, the article stated that the Dutch established themselves in what eventually became New York City and grew to dominate the Atlantic slave trade of the early 17th century. Eventually the British took control over the colony in 1664, and they replaced the Dutch as the world’s leading slave traders, bringing slaves into the colony through New York City. While the city served as a central hub for northern slave trade and subsequently increased the number of enslaved people, it also became a beacon of freedom for those escaping bondage. As the number of fugitives and free people in the city grew, however, so did the number of disgruntled owners and slave catchers looking to take any African American back to the South, no matter the status of free or fugitive. The growing epidemic of kidnappings forced some African Americans to make the choice of staying in the city or moving farther upstate or into Canada.

Accompanying the increasing number of free and fugitive people were discussions regarding abolition within the state. Foner’s article states that Vermont was the first state to outlaw slavery in its state constitution in 1777, and it was not long after till other northern states began to follow suit. New York broached the subject in 1777 with the proposed idea of gradual emancipation, but “nothing came of the idea.” Again the slavery debate was brought up to the state legislation in 1785, and a bill that would allow for gradual emancipation while still prohibiting free African Americans from voting, holding office, or serving on juries was passed by both the House and Senate. It was vetoed, however, by the state’s Council of Revision because it went against “the revolutionaries’ own principle of no taxation without representation.” Finally, by 1799, New York adopted legislation that would bring about abolition, but it was to be done gradually and did not apply to those already alive and enslaved. In 1817 an amendment was made, and those that had been enslaved prior to 1799 would be granted their freedom on July 4, 1827. While many of the slave owners decided to privately manumit their slaves before 1827, there were still almost 3,000 people enslaved when it was officially made illegal in New York.

In the midst of the long and drawn out fight for abolition in New York was the dedication of a cemetery specifically for the African Americans of Kinderhook. A small town first noted on Dutch maps sometime between 1614-1616, the Town of Kinderhook’s website states that the area was a “distinctive enterprise” where residents made a living on farmland and sawmills. The town also had residents that participated in the owning of slaves, with the 1790 census showing 638 out of 4,661 individuals living in the area were enslaved people. The cemetery—established in 1816—came at a time when there would have been a growing number of free people in the town, and Rogers made it perfectly clear in his will that he was donating one fourth of an acre of land for them to use as a cemetery.

After it ceased being an active burial ground, the land went through times where little care was given, but since 1990, the Village of Kinderhook has made an effort to maintain the area. Since the installation of the marker in 2016, multiple headstones can still be seen, though some of the inscriptions have been worn away.