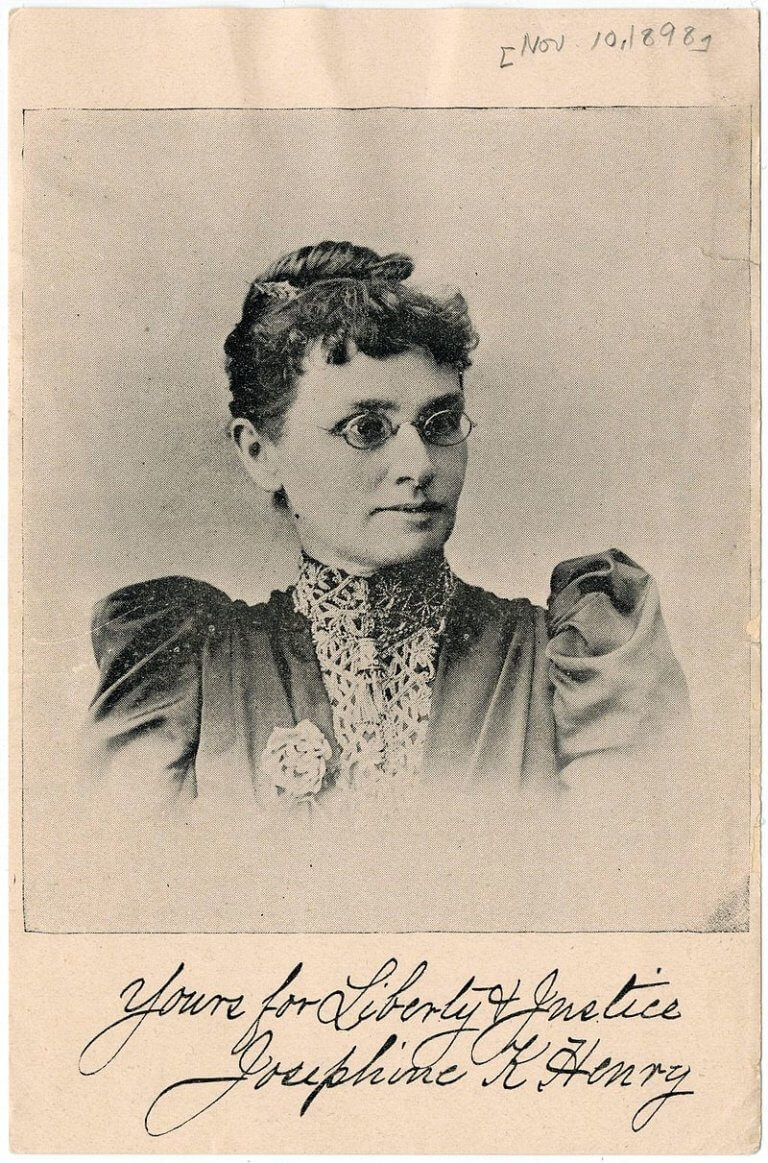

JOSEPHINE HENRY

- Program

- Subject

- Location

- Lat/Long

-

National Votes for Women Trail

-

People

- 210 Montgomery Ave, Versailles, KY 40383, USA

- 38.0478992, -84.7262096

JOSEPHINE HENRY

Inscription

JOSEPHINE HENRY1843-1928

HOME OF SUFFRAGIST, AUTHOR,

ORATOR AND TEACHER WHO

LOBBIED FOR EQUAL RIGHTS

FOR ALL WOMEN.

WILLIAM G. POMEROY FOUNDATION 2018

A prominent suffragist in Kentucky, Josephine K. Henry worked not only to get women the right to vote but for equality among their male counterparts in all areas of political and social life. Said to have grown up in a house that encouraged independent thinking, Henry fully embraced that attitude, and as a result, became involved with movements for women’s equality on both a national and state level. Henry was also vocal about her displeasure with the Christian faith, contributing her own comments to Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s The Woman’s Bible, and in continuation of the fight for female recognition, became the first woman in the South to run for a state office.

In an article written about Henry for the Blue Grass Blade on February 23, 1908, it is stated that her goals had always been “securing consideration and a measure of justice for her suffering sisters.” In consideration of those goals, Henry was involved with organizations on both a state and national level, working with them to gain the vote for women, as well as equality for women under the law. Her dedication to political reform drove her to run for political office, having been the Prohibition Party candidate for clerk of the Supreme Court for Kentucky. Henry’s political aspirations continued to expand, and an article from the New York Times on November 15, 1897 declared that she was a possible presidential candidate for the 1900 election. Listed as part of her party platform was the enfranchisement of women, recognition of Cuba as an independent nation, and the abolition of liquor traffic.

One of her greatest achievements, according to a short piece written by Aloma Dew for Kentucky Women: Two Centuries of Indomitable Spirit and Vision (1997), was the passing of the Married Woman’s Property Act (also known as the Husband and Wife Bill). Up until the implementation of the bill in 1894, women in Kentucky were unable to make wills, be guardians of their children, receive wages they had earned, and own or inherit property. The bill was considered to be “anti-family and unladylike,” but in Henry’s own retelling of events as part of the minutes for the 7th Annual Kentucky Equal Rights Association Convention in 1894, she proclaimed that married couples finally “have exactly the same interest in each other’s estate.” It was stated that the bill was the product of “years of toil, sacrifice, and expenditure of vitality and money,” and in order to see it passed, Henry had to make a speech to the Kentucky Legislature that made sure the “dead property rights bill was resurrected and passed.”

As a proponent for women’s suffrage, Henry’s views were expressed in multiple publications through her writings, with an example being a piece she had published in The Arena in 1895 (vol. XI). Entitled “The New Women of the New South,” Henry’s goal with the article was to emphasize the idea that many women in the South were in favor of getting the vote. She stated that for so long women of the South were influenced by their environment, writing that it was “questionable whether [they had] any clearly outlined opinion, exclusively [their] own.” Due to what she called oppression by “the masses of average men,” it had taken some time before women of the South decided to fight for a change in customs and laws that made them disadvantaged compared to men. These laws, Henry stated, saw women taxed without consent, their property confiscated, and young girls married to older men due to low age of consent restrictions. The women believed that if they were given the right to vote, they would finally have a say in the way they were governed, with Henry writing that voting was a “right secured from the same source that denies to woman the power to destroy them.”

As of 2019, the marker that stands in her honor was placed in front of her former home in Versailles, Kentucky.