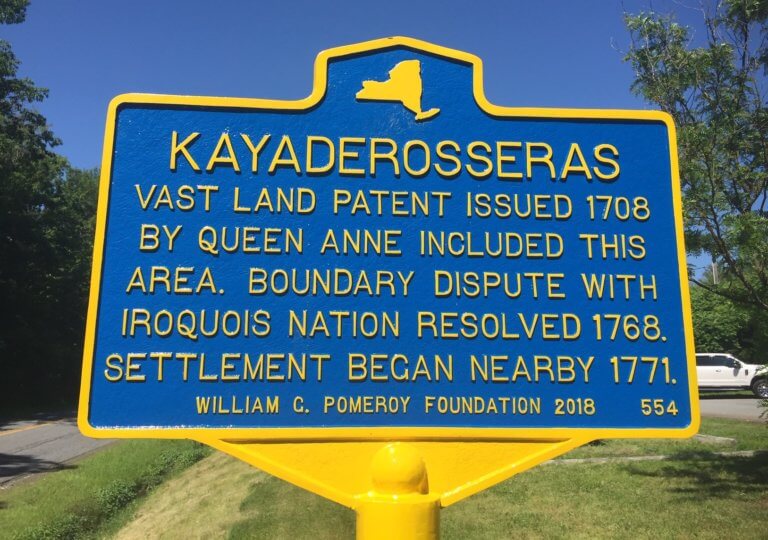

KAYADEROSSERAS

- Program

- Subject

- Location

- Lat/Long

- Grant Recipient

-

NYS Historic

-

Site

- 59 Outlet Rd, Ballston Lake, NY 12019, USA

- 42.957126, -73.851597

-

Saratoga County

KAYADEROSSERAS

Inscription

KAYADEROSSERASVAST LAND PATENT ISSUED 1708

BY QUEEN ANNE INCLUDED THIS

AREA. BOUNDARY DISPUTE WITH

IROQUOIS NATION RESOLVED 1768.

SETTLEMENT BEGAN NEARBY 1771.

WILLIAM G. POMEROY FOUNDATION 2018

Modern day Ballston Spa is located in what was once the Kayaderosseras Land Patent. A group of 13 English colonists claimed they had legally bought land from the Kanienkehaka, or Mohawk Nation, a member of the Haudenosaunee (commonly called the Iroquois Confederacy or Six Nations). The English claimants then applied for and were granted a patent of over 800,000 acres of land by Queen Anne in 1708. However, the Mohawks asserted that the sale was not made legally, that it would deprive them of hunting grounds vital to their livelihoods, and that the patent described a vastly larger area than in the original deed. As years passed and the colonies grew, English settlers began to encroach on the land claimed under the patent, which the Mohawks insisted was fraudulent. The land dispute lasted for six decades, during which the British Superintendent of Indian Affairs, William Johnson, repeatedly urged the colonial government and the Crown to invalidate the patent to avoid alienating Britain’s Haudenosaunee allies. His appeals were ignored until 1768 when Henry Moore, the colonial Governor of New York, decided to try resolving the dispute himself. He failed to do so, but authorized William Johnson to negotiate a deal and the boundary dispute was finally resolved that same year. A few years later, in 1771, Ballston Spa was founded.

The land west of the Hudson River that made up the patent was called Kayaderosseras by the Haudenosaunee peoples who lived and hunted there. This may be from an Iroquoian word meaning “lake country,” and hunters from all the nations of the Haudenosaunee would reportedly come to this region in the summer months to harvest from its bounty of game animals. (Historical Sketches of Northern New York and the Adirondack Wilderness, Sylvester, 1877)

In the spring of April 22, 1703, Samson Shelton Broughton, Attorney General of New York, obtained a license from the Colonial Governor for him and his company to purchase the land called Kayaderosseras. The Mohawks gave them a deed certifying the purchase on October 6, 1704, and an initial deed from 1702 was abrogated. Several years later, on November 2, 1708, a patent was granted by Queen Anne to 13 claimants, in order to validate their purchase from the Mohawks. This patent was called Kayaderosseras, or alternately Queensborough. However, Mohawk Hoyenah, or chiefs, said that agents of the purchasers told them the deed only covered enough land for a decently sized farm or two (Sylvester, 1877), not the over half a million acres of their best hunting grounds that the patent claimed. (Kayaderosseras Patent, 1708)

While the dispute festered, British relations with the Haudenosaunee declined under the inept management of Indian Affairs from Albany. Principal among the causes for this decline was the issue of fraudulent land claims, particularly the patents of Connojohary, Oneida Carrying place, as well as Kayaderosseras, among other problems. The situation grew so tense that William Johnson, the former British Superintendent of Indian Affairs, had to be called back into service despite having left because of a payment dispute with the British Crown. His reputation among the Haudenosaunee was strong enough that he had an honorary Iroquoian name, and they demanded in 1754 that Johnson represent the British if relations were to continue. Upon returning to his post in 1755, Johnson immediately convened a meeting with delegates of the Haudenosaunee to convince them to continue their alliance with the British. (Wraxall to Johnson, 1755) The French and Indian War had begun the previous year, and the Haudenosaunee were an invaluable ally for the British against the French and their Indian allies.

Johnson was unable to convince neither the Governor nor the assembly to take any action to dissolve the patent. Despite legal precedents for such an act, the assembly claimed that clearing the patent would “impinge” on the character of the Governor. The few settlers squatting on the patent balked at warnings of expulsion or legal consequences, augmenting tensions with the Mohawk. (Johnson to Earl of Shelburne, 1766)

Johnson fell ill in 1768 and went to convalesce near the ocean in Connecticut. Ironically, it was during this time that Governor Moore decided to again convene a meeting at Johnson’s estate near Lake Champlain, this time with both Mohawk representatives and agents of the patentees. (Moore to Earl of Hillsborough, May, 1768) The meeting quickly broke down, however, and the Governor had to end it abruptly to avoid an altercation. The meeting failed, but it did prompt the Governor to have the territory surveyed, an important step which prepared the ground for the final negotiations to succeed. (Moore to Earl of Hillsborough, July 1768)

On August 17, 1768, both Henry Moore and William Johnson sent letters to the Earl of Hillsborough informing him of Johnson’s success in facilitating an agreement. After reviewing both the original deed and the surveys commissioned by Governor Moore, the agents of the patent holders agreed to relinquish claims to much of the western side of the patent. In return for a payment of 5000 dollars, the Mohawk agreed to cede the remainder of the patent to the claimants. (Moore to Earl of Hillsborough, August, 1768) In March of 1772, the former patents of Kayaderosseras and Saratoga were combined under the name of the latter, and English settlers began erecting their first legal homesteads. (Sylvester, 1877)

While this compromise settled the legal claims between the parties, it cannot be said that both sides benefited unequivocally or on equal terms. Among the officials of the Colonial government, including Johnson, the Lords of Trade, and the governors of New York, and others, there was an explicit awareness that property speculators intentionally applied for oversized patents which they had no plans to settle and which they knew infringed on the territory of Indian nations. They were often granted these patents on the basis of fraudulent deeds obtained by intoxicating Indians who had no authorization or title to their nation’s lands. It was common practice for these patentees to wait until Indians were forced to move or died off before selling the lands at a premium, or to sell them to impoverished and desperate settlers without informing them that Indians held claim to the land they were squatting on. (Johnson to Lords of Trade, 1763)

This same pattern repeated itself in the case of Kayaderosseras. While the patent holders waited for 60 years, the Mohawk nation continually allied with the British and fought against their enemies at great human and financial cost, including in the French and Indian War (1754-1763). The British gave constant assurances that the issue would be settled, yet even after the French and Indian War, the colonial government and the crown never took any action. (Johnson to Lords of Trade, 1764) The Mohawk ended up ceding land they never agreed to sell in the first place in order to gain some kind of security against future encroachments. This made sense when the British maintained the Proclamation of 1763, which forbade settlement beyond a line drawn across the map of North America, even if it had failed to deter squatters on the Kayaderosseras Patent. (Johnson to Earl of Shelburne, 1766) The defeat of the British in the American war of Independence negated this proclamation line however, and the Mohawk were displaced from most of their lands.

As of 2018, a historic marker funded by the William G. Pomeroy Foundation stands on land that was once part of the Kayaderosseras patent to commemorate the resolution of the land dispute.