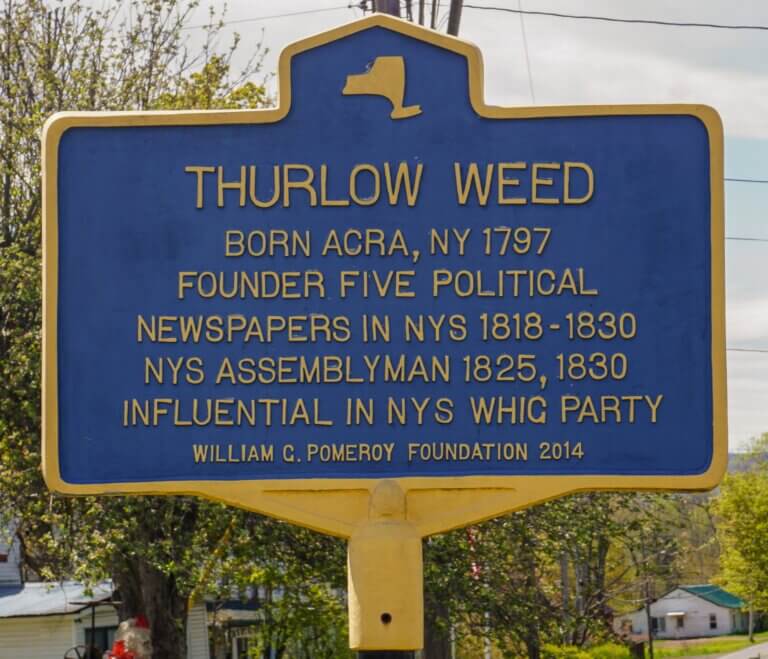

THURLOW WEED

- Program

- Subject

- Location

- Lat/Long

- Grant Recipient

-

NYS Historic

-

People

- 487 Old Route 23, Acra, NY

- 42.310505, -74.053831

-

Cairo Historical Society

THURLOW WEED

Inscription

THURLOW WEEDBORN ACRA, NY 1797

FOUNDER FIVE POLITICAL

NEWSPAPERS IN NYS 1818-1830

NYS ASSEMBLYMAN 1825, 1830

INFLUENTIAL IN NYS WHIG PARTY

WILLIAM G. POMEROY FOUNDATION 2014

Thurlow Weed (1797-1882) was a New York newspaper publisher and Anti-Masonic, Whig, and later Republican politician. Born into poverty in the hamlet of Acra, Weed apprenticed as a young child in the printing industry. He eventually launched five influential political newspapers in New York State, including the Norwich Agriculturist, Onondaga Republican, Rochester Daily Telegraph, and Anti-Masonic Enquirer. His last paper, the Albany Evening Journal, played an important role in the political campaign of William H. Seward who became Governor of New York State. Using the power of the pen to sway opinions of his readership, Weed was instrumental in the presidential nominations of William Henry Harrison (1840), Henry Clay (1844), Zachary Taylor (1848), Winfield Scott (1852), John Charles Fremont (1856) and Abraham Lincoln (1860).

Weed reports in his autobiography that he was born in the village of Acra, within the town of Cairo, New York on November 15, 1797. His parents, Joel Weed and Mary Ells Weed, were from Connecticut and Thurlow was the eldest of three brothers and two sisters. J.B. Beers wrote in 1884 that Thurlow’s father was among the early settlers of Cairo and built his home near the race track. While it is sure that Thurlow was born there, the location of the former log home is disputed and it was rumored that Weed visited the town some years prior to his death and attempted to find the site of his father’s homestead. (J.B. Beers, 1884)

The Dictionary of American Biography, published in 1936, writes that the Weed family moved away first to Cortland County, then to Onondaga County, where a young Thurlow began apprenticing at a print shop. He spent the next several years working in print shops across Central New York, as well as a brief stint in the militia service in 1813. In 1817 he became a foreman of the Albany Register where he first had the opportunity to write some news items as well as editorials, in which he supported DeWitt Clinton’s canal policy. (Dictionary of American Biography, 1936) He married Catherine Ostrander from Cooperstown on April 26, 1818.

For the next four years he attempted to start “Clintonian” newspapers in Norwich and Manlius, called the Agriculturalist and the Onondaga Republican respectively. Both failed, and he subsequently moved to Rochester where he was hired by the Rochester Telegraph. Here he wrote editorials supporting the presidential campaign of John Quincy Adams. (Dictionary of American Biography, 1936) Thurlow Weed claimed in his autobiography that the subscribers of the flopped Norwich Agriculturalist took their subscriptions to his later papers. (Autobiography, 1883)

Thurlow Weed’s rapid rise to prominence began when the Rochester Telegraph sent him to Albany to lobby for a bank charter in 1824. There he involved himself more intimately in politics, working with Clay and Adams and becoming essential to the Anti-Masonic Party. Soon, he was campaigning across the western counties of New York for both the gubernatorial campaign of Clinton and Adam’s presidential campaign (Dictionary of American Biography, 1936), and was elected to the New York State Assembly himself in 1925 and again in 1830, representing Monroe County. (Civil List…1891)

In 1826 he gave up the Rochester Telegraph to instead focus on publishing the Anti-Masonic Enquirer. Weed boasts in his autobiography that by 1828 this paper had a circulation apparently spanning the central and northern counties of New York as well as five counties in Pennsylvania and the entirety of the state of Vermont. In 1830 the first issue of the Albany Evening Journal was published, with Weed serving as its primary creator, editor, and manager, and this paper would become the cornerstone of his career for over 30 years. (Dictionary of American Biography, 1936) He describes the founding of this paper in his autobiography as a triumph against warnings that it was unwise to attempt building another paper in Albany, where it would compete with the Daily Advertiser and the Argus, two older and more established papers. His influence played a notable role in the elections of William H. Seward to the Governorship of New York in 1838 as well as Harrison’s election to the presidency in 1840.

The Dictionary of American Biography describes his position of influence at this time: “Weed was now generally regarded as the dictator of his party [Whigs], and was charged with dominating Seward, to whom he was bound in closest personal friendship.” As the book notes, Weed’s influence was primarily through patronage and political machine campaign tactics; he was not particularly ideological.

Weed remained at the height of his influence until Seward was defeated in 1842, and after the presidential campaign of 1844 he traveled and even contemplated giving up his Evening Journal. The death of President Zachary Taylor in office and the succession of Millard Fillmore in 1850 spelled a significant decline in Weed’s political fortunes, as he and Seward had aligned themselves against the Compromise of 1850 while Fillmore accepted it. This played a decisive role in permanently splitting the Whig party, ultimately leading to its dissolution. (Dictionary of American Biography, 1936)

In later years Weed remained an influential if divisive public figure, and was consulted by politicians going on the campaign trail, including most notably Abraham Lincoln. He and Weed corresponded and talked on many occasions after Lincoln began consulting him for his presidential run. Despite his role in aiding Lincoln’s campaign, Lincoln and Weed remained at arm’s length politically as Weed accepted the unsuccessful Crittenden Compromise of 1861, which sought to preserve the Union by constitutionally recognizing slavery as legitimate in the South. Lincoln and the growing radical Republican faction opposed it.

In 1863 Weed finally gave up the Evening Journal and moved to New York City where he became the editor of the Commercial Advertiser in 1867. However his return to journalism proved brief as failing health and eyesight caused him to retire, though he would continue contributing editorials on politics as well as consulting with politicians. (Dictionary of American Biography, 1936)

Thurlow Weed died on November 22, 1882 at the age of 85 and is buried in the Albany Rural Cemetery in Menands, New York. (Headstone, Albany Rural Cemetery)